After three days by ourselves in Yagasa, we took the short jaunt to Fulaga. Fulaga/Vulaga, pronounced Foo-Langa, is such a special place and the community does a fantastic job of sharing their subsistence living, history and heritage. After presenting kava and the sevusevu ceremony, cruisers are assigned a host family to extend the welcome and deepen the connection.

Fulaga is the southern-most inhabited island of the Southern Lau Group with a population of about 400 residents spread throughout three villages. A coral reef surrounds the island and one narrow passage through the reef provides access to the lagoon which is about 6 NM x 5 NM. The lagoon is populated with hundreds of mushroom islets above the water, hundreds of coral boomies below the water and many sandbars in between. In addition to all our technology, eyeball navigation is a must.

After assuring that Tieton was well anchored, we donned our sulus, proceeded ashore and walked into town with our kava. As we approached the village, we removed our hats, sunglasses and backpacks, which can be seen as offensive. Seta was the first villager we encountered and he greeted with a boisterous “Bula! Bula!” (Hello! Welcome!). He told us he’d show us the visi wood carving shops, for which the island is known, and then take us to the chief. Along the way, he told Bill to pick some coconuts, which Bill later served us when he was assigned as our host family.

The patience and slow pace was almost overwhelming. Seta took about two hours to introduce us to the community and along the way we were welcomed by every person we encountered.

Kava and Sevusevu

By ancient tradition, visitors are expected to bring a gift of kava to present to the village chief. It is a sign that we come in peace and will be respectful of their property, which includes the land, lagoon, surrounding reef, and all the water, plants and animals within it. Upon our arrival at the chief’s house, Seta chanted to the chief and then beckoned us inside. After removing our shoes, we proceeded inside and sat on the mat in front of the chief. Men sit cross legged with sulus covering their knees and women sit with their knees to the side.

After a lengthy liturgy in Fijian, Seta presented our kava to the chief, which the chief accepted and then started with his own lengthy liturgy. Then, in English, the chief thanked us for our gift and said that in the sevusevu ceremony that just occurred we’d been welcomed to the island, which we could now consider our home and village and we were now part of their community. We could take all the fish and coconuts we wanted, and we could go anywhere we pleased. We were invited to church on Sunday, and advised that no water sports were allowed, except for swimming around the boat. Hearing the ceremony then understanding the meaning was incredibly moving.

They talked a bit about their families and village. We were then asked to share where we came from and tell them about our family.

Seta explained that he’d asked the chief special permission to assign Bill as our host family. Bill’s father had recently passed away and Bill was stepping into his role of the family patriarch, with support and coaching from the community. Bill and his girlfriend Amelia would serve as our host family, which we expressed was perfect because our children are about the same age as Bill.

Our Hosts Bill and Amelia

When we arrived at Bill’s home, Bill welcomed us and gave us fresh coconuts he’d just harvested, along with a papaya stem straw to drink it with. The papaya stem must have been the prototype for our store bought straws, except that they soften after a day and are biodegradable. Perfect! We made arrangements to return the next day for a hike and to meet Amelia.

The next day was rainy, so Bill apologetically suggested tea instead of a hike. He lit a fire in the grill, using half of a coconut shell with hot coals gathered from a neighbor. While Amelia grilled hot crepe-like pancakes, Bill made tea and explained how he’d picked and dried the lemon tree leaves the prior day. They invited us to lunch after church on Sunday, and we made arrangements to meet them at the beach the next morning, which was Saturday.

A fairly large group of people gathered at the beach the next day to await the return of local delegates who’d traveled to witness the installation of a new president of the Lau Group. We were told Bill was in the village preparing lobolo, the island’s fish and coconut dish, to be consumed later that day at the village celebration. Later, Bill and Herman took our dinghy to get clams, while Amelia and I harvested nama (grape seaweed). Amelia showed me how to pull the seaweed, and we did a preliminary wash at the beach. Later she would pluck the grape clusters from the vines, complete the cleaning, rinse in fresh water, and then do a final rinse with hot water.

At the Methodist service, children sat in the front pews under the congregation’s watchful eyes. The minister emphatically delivered his sermon, none of which we understood. A parishioner briefly welcomed visitors in English. Most enjoyable was the booming singing and watching some of the children discretely (or not) plug their ears.

After church, we went to Bill and Amelia’s for lunch. While Amelia prepared lunch, several community members dropped off food. Bill inherited his father’s role to serve as the gathering place for food that Bill subsequently delivers to the minister, school officials, or community celebrations. After his delivery, Bill joined us for a delicious lunch of taro, potatoes, curried crab, and cold soup. The soup was made with chopped clams, onion, fresh squeezed coconut milk, grape seaweed and lemon juice from lemons harvested the previous day. Herman was delighted to have Amelia crack and pick his crab (I’m allergic), and Amelia ate only after Herman finished. Without refrigeration, perishable food must be prepared and consumed the same day. Leftovers were stored temporarily in the non-functioning oven (no electricity), and they expected community members would stop by to eat them. Nothing goes to waste as shells are returned to the beach and pigs enjoy the scraps.

After our hike with Bill the next day, Amelia prepared what she called scones, made in a sheet pan with fresh squeezed coconut milk, lemon juice, sugar, and flour. She baked the cake next door in her grandparents’ oven, for which they were rewarded with a couple pieces. We ate our share and when we were done, three schoolboys on their lunch break wandered by and were happy to have leftovers.

That evening, Bill and Amelia joined us for dinner on Tieton. They seemed to enjoy the salad and eggplant caponata with pasta and meatballs. Amelia was pleased that I harvested my own grape seaweed for the salad.

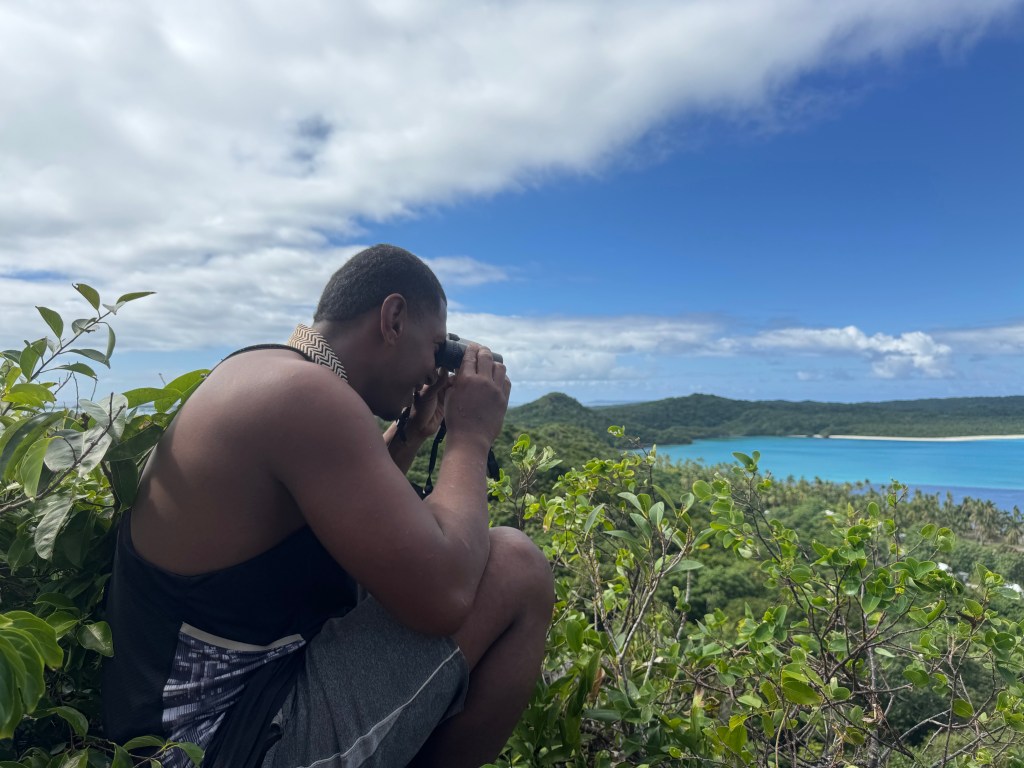

Bone Cave and Lookout

Until around 1870, villagers lived in a ravine behind the lookout, where it was easier to protect the women and children from marauding tribes from other islands. Pieces of limestone stacked nearby the lookout were thrown at any enemies climbing towards the village. As we were climbing the hill, I could completely imagine how vulnerable the enemies would be. Given that the natives practiced cannibalism, I’m sure they found the enemies to be quite delicious once their heads were smashed in.

From the lookout we could view most of the reef surrounding the island, including the pass we came through. It was fun to watch four sailboats come through the pass. The southeast anchorage we planned to move to the next day was also visible, along with our mast where we were currently anchored.

When the villagers moved closer to the shore, the bones from their deceased ancestors were left in the cave where they remain today.

What’s Next

We’ve enjoyed our connections in Fulaga and plan to stay a bit longer, although we’re going to a different anchorage.

Leave a comment